FAMOUS PEOPLE

WHO HAVE DONE SOMETHING ON EARTH TO HELP OTHER PEOPLE

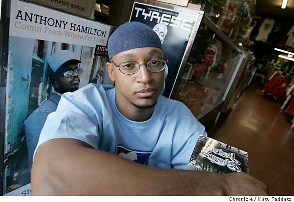

Hip-hop's political 'Swords'/Journalist Adisa Banjoko explains how the

community can create political change in his new polemical book

Joshunda Sanders, Chronicle Staff Writer

Adisa "The Bishop of Hip-Hop" Banjoko, one of the Bay Area's pioneering

hip-hop journalists, has been writing about the culture for insider

magazines like the Source, XXL, Rap Pages, 4080 and Bomb for almost 20

years. He wrote a history of hip-hop's four elements -- graffiti, break

dancing, DJing and rapping -- for the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts'

touring "Hip- Hop Nation" three years ago, and was even briefly at the

helm of a "Chicken Soup for the Hip-Hop Soul" book project. This year,

freed from the constraints of magazine assignments, he completed his new,

self-published book, "Lyrical Swords: Hip Hop and Politics in the Mix."

Not that Banjoko, 34, has been a follower for his whole career. His

father, the first person to buy him a turntable and teach him how to

scratch records like a DJ, also exposed him to the Malcolm X speeches

quoted in Public Enemy's records. He always nurtured a love for hip-hop as

a catalyst for political and artistic change. As a teen, he made friends

with fellow San Bruno residents Mixmaster Mike of the Beastie Boys and

mix-tape maestro DJ Vlad, and attempted to B-boy (break dance).

He got his start as a hip-hop journalist at 17, when a teacher persuaded

him to write for the Oceana High School paper, the Foghorn. After

listening to "My Uzi Weighs a Ton," a song by the then-unknown rapper Eazy

E, Banjoko called a number listed on the B-side. "I left him a message

that said, literally, 'Hi. I work for a big-time newspaper and I want to

interview you,' " Banjoko recalls with some embarrassment. "And he called

me back! He gave me his home number."

And so it began. Banjoko became one of the first writers to chronicle Bay

Area hip-hop culture, writing about such local heavyweights as Paris, Too

Short and Digital Underground at the same time the genre's popularity grew

on the East Coast. When he started out, he said, he never aspired to be

the type of fluff-producing celebrity journalist whom hip-hop culture has

endorsed over the past 25 years, but to be the type of person who "writes

down what most people think and don't say."

He still does. Even as he juggles life as a stay-at-home dad with his

public relations work for the Riekes Center for Human Enhancement in Menlo

Park, a nonprofit mentoring organization, he remains an iconoclast.

Recently, months before hip-hop pioneer KRS-One was maligned in the press

for saying that black people cheered after Sept. 11, Banjoko challenged

him to a public debate. KRS-One had previously come to the Bay Area and

advocated hip-hop as a cultural and political force transcending

ethnicity, elaborating on his famous line: "Rap is something you do;

hip-hop is something you live."

"After listening to him talk about 'being hip-hop,' for a few years,"

Banjoko said, "I realized it was baseless." (KRS-One declined the

invitation to debate; he did not respond to interview requests for this

profile.)

Banjoko believes KRS-One turned down a public debate because he has too

much to lose. "It's not a beef; it's a philosophical challenge," he

maintains.

A study in contrasts

Banjoko calls himself "Urkel in a kufi" one moment, then quotes from

Plato

and the Quran the next. He gave himself the moniker Bishop of Hip-Hop,

however, in honor of his favorite chess piece, not because he thinks he's

some sort of high priest.

He has the gracefully lanky build of a basketball player but the round-

framed glasses of a geek. His goofy grin and easy wit are disarming,

especially when he launches into bragging about his martial arts skills;

then the smile disappears and the married father of two begins to explain

his devotion to Islam. He combines a disdain for hip-hop's current

materialism with the nostalgia of an ex-rapper. In his new collection, he

describes his introduction to the culture as a B-boy: "I chose that 'cuz

you didn't have to have money to be a B-boy. You just needed heart,

discipline and the courage to go out there and show the world what you

got."

The book offers concrete suggestions on how hip-hop fans can forge a

political movement from the culture, instead of just telling young people

to go out and vote. Banjoko also tackles misogyny and interviews respected

musicians like Q-Tip and Rakaa from Dilated Peoples. It's a far cry from

the hip-hop "journalism" on BET and MTV.

"Most hip-hop journalists are groupies with pens," he said recently over

lunch at a Thai restaurant in the Haight. "I don't need to be backstage

popping corks; I just need 10 minutes so I can ask these 10 questions. I

don't think hip-hop journalists take themselves or hip-hop that

seriously."

There are times when Banjoko seems to take himself too seriously, and

there are some missteps in the book -- nothing an editor couldn't have

fixed. But the book also includes enlightening essays that combine Eastern

wisdom with Western analysis; a good mixture of scholarship and street

wisdom.

"I know there are things in the book and things about me that are still

not very refined," Banjoko offers as explanation. "But I'm trying to be

dangerously human. I acknowledge that this is all I got. There are a lot

of people trying to run hip-hop, and it's too vast and too nebulous to be

run by anybody or any one personality, so I offer suggestions. Because I

allow myself to be flawed in front of other people, they don't feel so

bad, freaking out about hiding their own flaws."

Banjoko is not ashamed to write or talk about his imperfections. In high

school he was a slacker, rebellious and lazy. He liked to binge-drink on

weekends, dropped out of school and became "a couch-surfer" for a while.

All who wander aren't lost, though. After meeting former Black Panther

Kiilu Nyasha and starting to work on the Commentator, a Panther newspaper,

Banjoko earned his GED. Rappers Ice Cube and X-Clan were announcing the

end of rap's political era, Sistah Souljah was on "Donahue" and Rodney

King was beaten in Los Angeles. Banjoko said his soul was aflame. He

converted to Islam just before his 21st birthday.

He changed his given name, Jason Parker, to the West African Adisa

Banjoko

-- names that mean "one who makes his meaning clear" and "stay with me and

go no more," respectively. Around the same time, he met James Bernard, one

of the founders of the Source magazine, at a Chuck D talk at San Francisco

State University, and his hip-hop journalism career took off.

Local rap historian Davey D met Banjoko when the budding journalist was

also rapping. "(Banjoko) brings his own flavor to the game," D said. "His

perspective is fresh. ... You don't see a whole lot of people who have a

voice these days."

One reason, D said, is that big names in the entertainment industry do

not

respond well to criticism. Actually, they don't respond to it at all,

meaning that reporters who aspire to be objective in hip-hop journalism

may find themselves unable to talk to what D calls "marquee players"

(think P. Diddy).

What keeps Banjoko honest, he says, is that he is just one of the actors

in "God's divine play. I don't care about kicking it with any of these

fools (for any reason) other than getting information from them and

understanding them and trying to communicate what their music and their

message means to the community and hip-hop."

Writing his own way

There was a time when Banjoko floundered around, doing a bunch of jobs -

-

first, he was a paralegal, then a grocery clerk. He fell into public

relations for a dot-com and when he got laid off in 2000, he started his

own PR company. When he met Kyle Canfield, the son of "Chicken Soup for

the Soul" co-creator Jack Canfield, Banjoko was already embittered by his

forays into corporate America. When the book project fell apart around

2001 after creative differences between Kyle and Banjoko, he felt that he

could really trust only himself with his work and his vision from then on.

This is what he told Karen Johnson at Marcus Books when Banjoko and two

friends, Omar Ditona and fine artist Ed "Scape" Martinez, arrived in San

Francisco with a box full of "Lyrical Swords" to sell. Like many other

potential buyers on that breezy Thursday afternoon, she eyed the slim,

gray book while he told her about how the book came about after the demise

of the "Chicken Soup" collection.

Johnson listened thoughtfully, then took a stack of "Lyrical Swords" and

said, "I'm a black woman. We don't like chicken soup; we like gumbo."

Between his trip to the Fillmore and a brief Thai food lunch in the

Haight, Banjoko sold several books as he walked through the Haight wearing

a black shirt designed by Martinez with the words "They wanna kill

hip-hop" emblazoned on the back. He sold a book to an old-school DJ and

put some books on consignment at Future Primitive Sound before the group

headed back downtown.

All day, he'd been prompting Ditona to put Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat

Stevens) in the CD player, fluctuating between thoughtful pronouncements

about faith and giddy discussions about selling his book around the Bay

Area.

In the midst of heavy afternoon traffic, the guys started talking about a

recent trip to Bed Bath & Beyond. Suddenly, Ditona said, "They have these

things that make s'mores," and the car filled with hearty laughter.

"Oh, man," Martinez said, shaking his head in mock shame.

"If you're so lazy you need a machine to make s'mores, I don't know if I

can kick it with you," Banjoko began.

Then the group started in with more jokes about jujitsu, more nostalgia

about funnel cakes in the summer and, of course, the good old days of

hip-hop. As they headed south on Highway 101 toward home, Banjoko went

through his scrapbook of the old days in San Bruno. Earlier in the day,

Martinez had asked him how he felt about this new milestone in his career

-- a book of his work that isn't sponsored by any big-name magazine or

included in any anthology (even though Banjoko and DJ Vlad are still

planning to publish the work that would have been included in the "Hip-Hop

Soul" book).

"It's humbling," Banjoko said, in earnest. Then, with a chipper smile, he

noted that the box he'd brought to the city was empty. "Amazingly,

everything I saw Too Short do at Eastmont Mall really works."

For more information about the book and upcoming Bay Area readings, go to

www.lyricalswords.com.

E-mail Joshunda Sanders at jsanders@sfchronicle.com.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright 2004 SF Chronicle

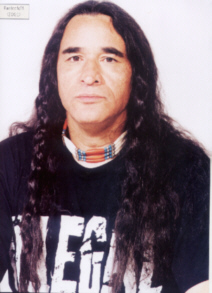

Ernie Paniccioli Bio

Regarded by most to be the premier “Hip-Hop photographer in America”, Paniccioli first made his foray into the culture in 1973 when he began capturing the ever-present graffiti art dominating New York City. Armed with a 35-millimeter camera, Paniccioli has recorded the entire evolution of Hip Hop. Much in the same way Gordon Parks recorded the Civil Rights Movement, or akin to the manner in which James Van De Zee, the documentary photographer of Harlem in the 1920s, met the energy and spirit of the times head-on with his picture-making. And like Edward S. Curtis’ monumental prints of the Native peoples of North America, himself a Native American, has found a beauty and resiliency in a community often ignored by mainstream society

From Grandmaster Flash at the Roxy (a popular Manhattan nightclub of the late 70’s and early 1980s), to the athletic moves of the legendary Rock Steady Crew, to the fresh faces of Queen Latifah, Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., Eminem, and Lauren Hill. Paniccioli has been in the forefront documenting the greatest cultural movement since Rock and Roll in the 1950s. A true renaissance man, Paniccioli is also a painter, public speaker, and historian. He has also photographed a number of popular figures beyond Hip Hop, such as Frank Sinatra, Liza Minelli, and John F. Kennedy, Jr.; Britney Spears; and Ricky martin, to name a few.

The Chief photographer for Word Up! Magazine since 1989, Ernie Paniccioli’s work has also appeared in The New York Times, Time, Newsweek, Life, Rolling Stone, Spin, Vibe, Ebony, and The Source and XXL. His television credits include MTV and VH1. Ernie Paniccioli’s images can also be found in numerous books, including: Turn Up The Volume: A Celebration of Black Music (UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History), Rap and Hip Hop, The Voice of A Generation (The Rosen Publishing Group). And Lift Every Voice and Sing (Random House). He was chosen by KrS1 to be the spokesman for The Temple Of Hip Hop at The United Nations at the Hip Hop Peace conference in May of 2001. He was also the moderator at the Meeting Of The Minds at the Zulu Nation 27th Anniversary.

His photography was on huge display outside the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for The Roots, Rhymes and Rage exhibit in 1999 and a featured part of that same exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2002.

He and Kevin Powell have a book documenting thirty years of his Hip Hop photography due out in November of 2002 called “Who Shot Ya” (Amistad Press)

“We the Hip Hop World Nation and

Beyond Earth must always respect our brother for what he has offered to our

World Hip Hop Nation and that is his science of taking fantastic pictures of

our Hip Hop World. All praise Due to the Supreme Force for our warrior,

father, thinker, teacher, speaker, historian, powerful photographer. The Hip

Hop Photo King”

Afrika Bambaataa, Universal Zulu Nation

“Mr. Paniccioli documented the only true representation of authentic Hip Hop

history to date. He photographed the rise of the greatest inner city

movement of the last 27 years of the 20th Century. The God of Hip Hop

photography.”

KRS1, The Temple of Hip Hop

“Ernie Paniccioli has been that archivist of the urban emotion covering the

years leading to the millennium and beyond. His work and integrity and

hustle have long provided that window to the Hip Hop world that was

necessary to exchange the culture way before big budget videos. We thank him

for pushing our faces to the world”

Chuck D, Public Enemy

“Truly the Master Photographer of Hip Hop”

Charlie Ahern, “Wild Style” and “yes yes y'all”

“... The career of photographer Ernie Paniccioli has documented the

remarkable thirty year hisory of Hip Hop. Many visitors to the exhibition

“Hip Hop Nation: Roots, Rhymes and Rage” at the Brooklyn Museum in 2000 had

the opportunity to see a small slice of his work. Now his entire career is

captured in the compelling photographs in this volume, along with an

autobiographical narrative presenting his life, from his boyhood on the

streets of Brooklyn to his role as the pre-eminent photographer of Hip Hop”

Arnold Lehman, Ph.D.

Director, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, New York

“...For Ernie Paniccioli to focus his camera on his subjects as well as make

successful environmenal portraits offers the reader a clearer understanding

of how Ernie's visibility as a photographer is respected in this community.

An impressive project, it will make an unique contribution to the complex

lives of photographers, hip hop culture, fashion and performance art...”

Deborah Willis

Author, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers

“An artist with a camera, Ernie Paniccioli's photographs have not only

documented but helped define hip-hop style. His understanding of where the

music has been and his beliefs regarding where it should go gives his work

an edge, a personality, that brings something special out of his subjects.

Ernie's passion comes through in his work, and the stories recounted herein

in word and images, gives us insight into the person behind the camera as

well as the subjects being photographed.”

Jim Fricke

Senior Curator, Experience Music Project, Seattle, Washington

DISCOGRAPHY

break.thru@comcast.net

Steven "Boogie" Brown

SINGLES |

ALBUMS |

|

6. Flashlight – Remake with P-Funk and Afrika Bambaataa

13. Rapper Dapper Snapper – Remix with Edwin Birdsong

Remake

|

Soundtracks:

1. King Of The Jungle 2. Naked Fear 3. Hip Hop For Kids Workout Video Winner Of The Parents Choice Award

TV & Radio Spots:

M.O.P

|

PRODUCTIONS |

MEMBER OF |

|

|

|

True Soldier of our Struggle has joined the ancestors.

BY

EricaQueens@aol.com

Mother of lynching victim Emmett Till dies

Mamie Till Mobley died at age 81.

January 7, 2003 — Mamie Till Mobley died Monday afternoon in Jackson Park Hospital at age 81. Her son, Emmitt Till, a young Chicago boy, was brutally murdered by racists in 1955 in Mississippi.

"Emmitt's death paved the way for some changed to be made. Some constitutional laws to be put on the books. And I think young people need to know what price was paid for the freedom we enjoy now," said Mamie Till Mobley on Memorial Day 2002, as she visited her son's grave.

Emmitt Till

Emmitt Till was beaten, shot and dumped in a river by Mississippi racists in August of 1955. In Chicago, his mother insisted there be an open casket so the whole country could see the brutality of racism. Many say that was the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement.

"Rosa Parks said it best when asked, 'Miss Parks, why didn't you go the back of the bus?' She said, 'I thought about Emmitt Till and I just couldn't go back,'" said Rev. Jackson.

On Tuesday morning Mamie Till Mobley's friends gathered at 71st and Wabash, a corner that is also known as Emmitt Till Road. They want Mamie's name to go up there, too, so she can be remembered for all she has done to keep Emmit's memory alive.

"There are Emmitt Tills all over this world. Kids ... those two kids down on 35th Street who have been missing for months. Maybe this is a call to action for all of us," said Ziff Sistrunk, friend of Mamie.

Ziff Sistrunk spoke with Mamie Till Mobley just yesterday. He recorded some of her last words.

"I guess we all think realistically about that day when we will be victimized by what is life's final common denominator ... that something we call death," said Mamie in 2002.

Mamie died of heart failure.